Huge Fines Are a Wake-up Call to Prioritize Data Security

Hoping to avoid fines and bad press, more companies are practicing “privacy by design,” according to a new survey. ISACA’s Safia Kazi parses the benefits and challenges.

The Illinois Supreme Court in mid-February ruled that White Castle System Inc. must face claims that it repeatedly violated the state’s Biometric Information Privacy Act by scanning fingerprints of almost 9,500 workers without their consent. The fast-food giant has said the ruling may cost more than $17 billion.

And last year, Facebook owner Meta Platforms agreed to pay out $650 million to settle claims it violated the Illinois law by collecting and storing the biometric data of the website’s users without permission.

Such whopping costs and consequences have been a wake-up call to more boards to prioritize data privacy, increase funding for it, and push for “privacy by design,” according to ISACA’s Privacy in Practice 2023, a survey of 1,890 constituents with certified cybersecurity or privacy backgrounds.

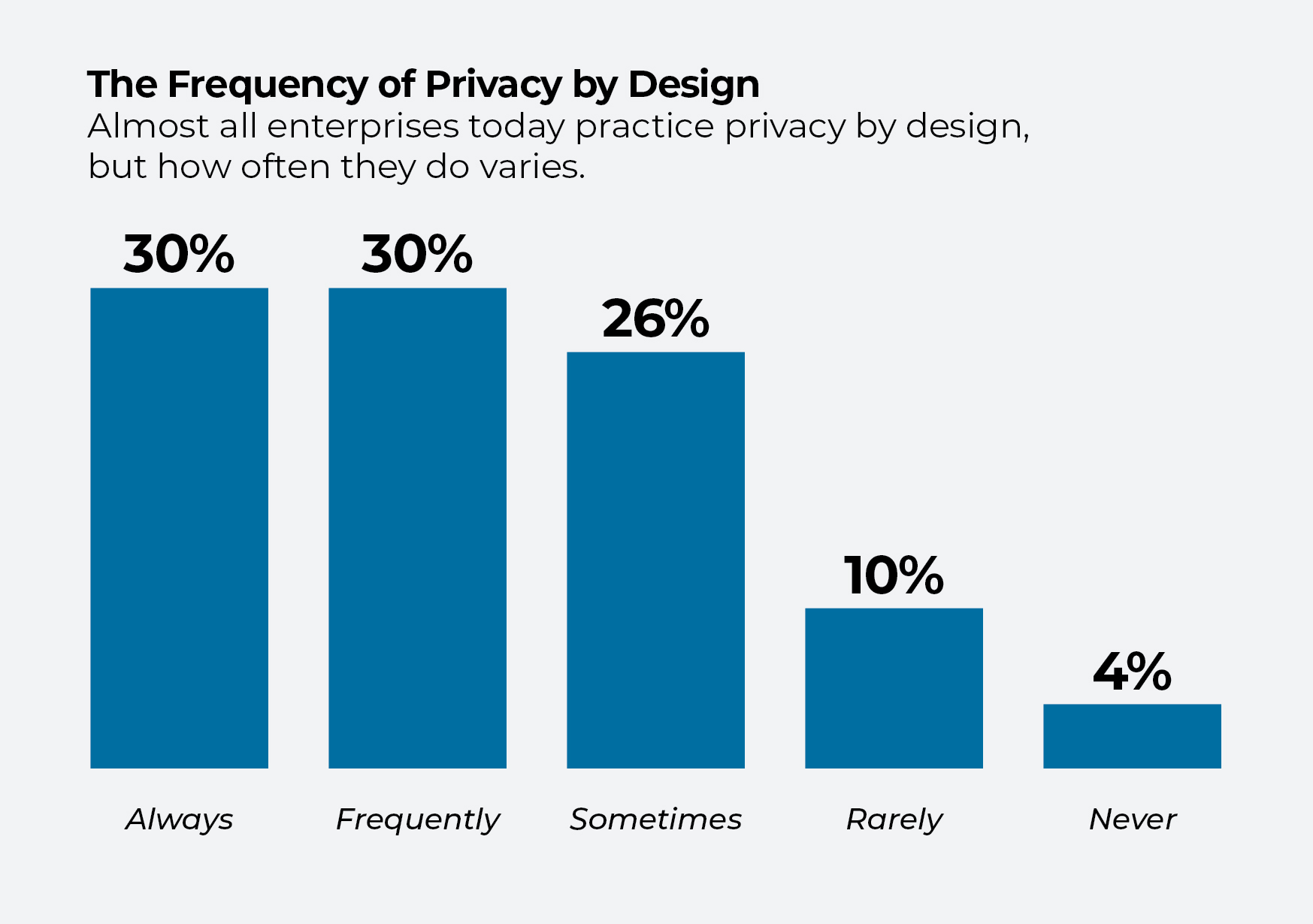

About 55 percent of respondents said their board is paying adequate attention to privacy. That’s reflected in the boost in companies practicing privacy by design—it increased to 30 percent, from 28 percent a year earlier—and the mean number of full-time employees with privacy-related work in an organization, which rose to 26 from 25.

“Privacy laws and regulations are having a really widespread impact,” says Safia Kazi, a privacy professional practice adviser at ISACA, the Information Systems Audit and Control Association. The boards are realizing that “organizations that aren’t compliant might see themselves making headlines because they weren’t doing the right things.”

People started receiving checks from Facebook because of improper use of biometric information. And they’re saying, “Wait a minute…. What exactly happened with my data?”

Kazi sees the laws and regulations prompting more emphasis on security not just because of potential liabilities for companies but also because they’re making consumers more conscious of how exposed their personal information may be.

“People started receiving checks from Facebook because of improper use of biometric information. And they’re saying, ‘Wait a minute: I got a $300 check from Facebook. Why was that? What exactly happened with my data?’” she explains.

With that growing awareness, consumers may make more informed decisions about which companies receive their business—and their data, Kazi says. “When they have multiple choices, they might pick the one that they know is actively doing a good job.”

In terms of data security, a “good job” means implementing both effective data privacy management (which relies on software to scan networks, cloud systems, endpoints, and apps to locate where sensitive data resides) and privacy by design (an increasingly important practice as we store and share larger amounts of personal data online).

[Read also: Managing risk in the age of data privacy regulation]

Companies that don’t place priority on data privacy will find themselves falling behind in the marketplace. “Your competitors might be doing a better job, and you’re going to be at a significant disadvantage if you don’t act,” Kazi says.

So what is privacy by design exactly?

Privacy by design means putting secure practices in place throughout the entire development cycle and maintenance of a project, starting with having privacy professionals involved in the selection of vendors.

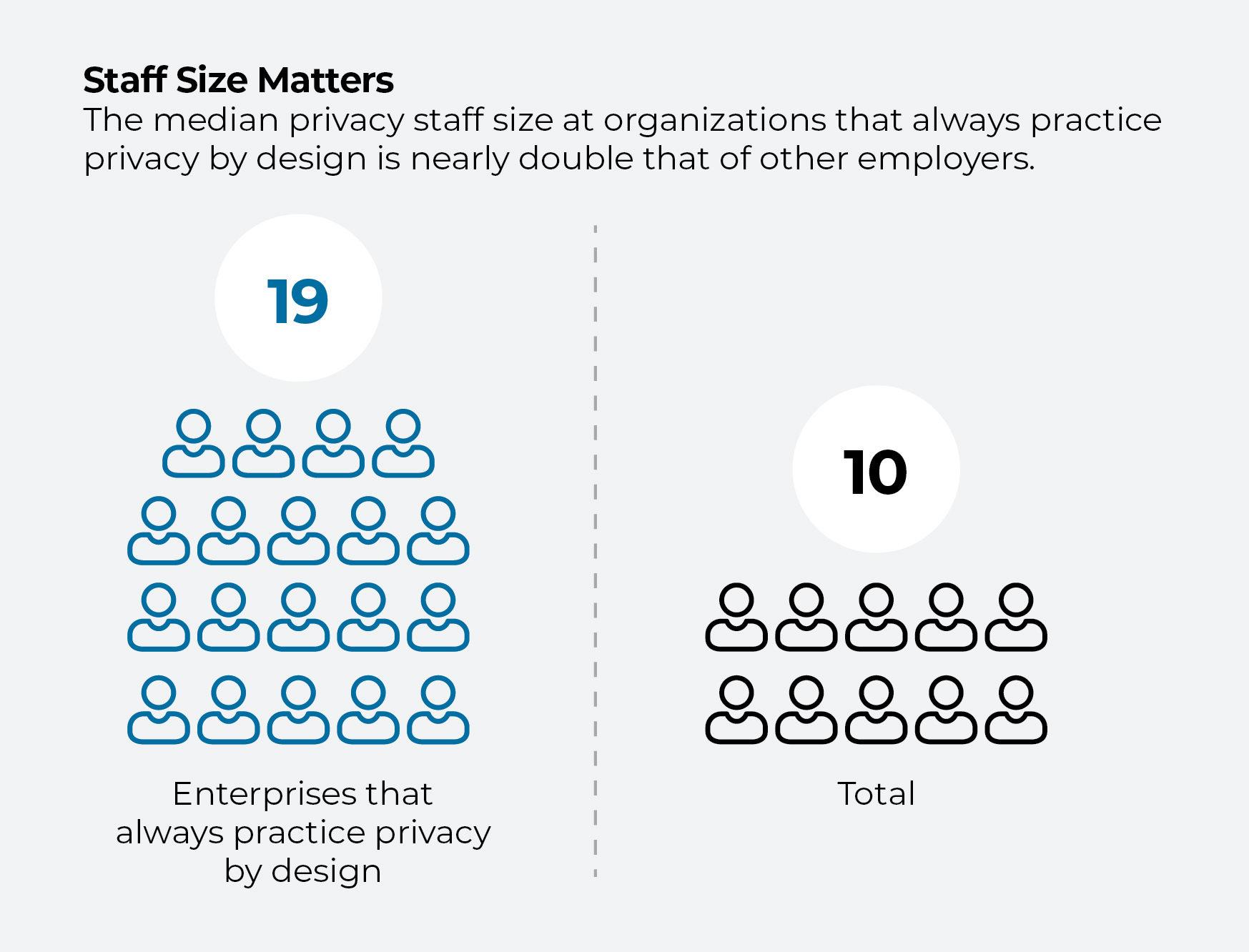

That takes manpower, of course. And companies that are practicing privacy by design tend to have larger staffs, respondents reported. Their median staff size was 19, compared to 10 from all companies. But some boards may not want to fund such staffing levels because they see privacy initiatives as a cost burden. Indeed, 42 percent of the survey respondents said their enterprise privacy budget is somewhat or significantly underfunded.

[Read also: Leaner budgets and larger layoffs could spur a new wave of insider threats]

Potential legal liabilities and bad press alone should lead companies to prioritize and incorporate data security right from the beginning, but making privacy an afterthought can also make a project much more expensive. If the privacy professionals step in late in the process and spot serious flaws, Kazi says, “it’s going to involve a lot of rework—potentially having to find new vendors or significantly change the way systems are operating.”

Privacy staffing shortages persist

Even though the mean number of privacy professionals in a company rose slightly, staff shortages continue to be a major issue.

Technical privacy roles remain more understaffed than legal/compliance roles, with 53 percent of respondents indicating they are somewhat or significantly understaffed on the technical side. That compares with 44 percent saying they are understaffed on the legal/compliance front.

“A lot of organizations want to hire this perfect unicorn who has years of legal experience and maybe has a law degree and they understand all laws and regulations but they’re also highly technical,” Kazi says. “I think organizations need to be realistic.”

About half the respondents are training non-privacy employees to fill the gap, while almost 40 percent are increasing their use of contract workers or outside consultants.

Kazi believes the best way to fill the gap would be to have existing workers who want to move into privacy shadow consultants for several projects or a length of time, so when the consultants move on, the workers have the knowledge and experience to continue in their place.

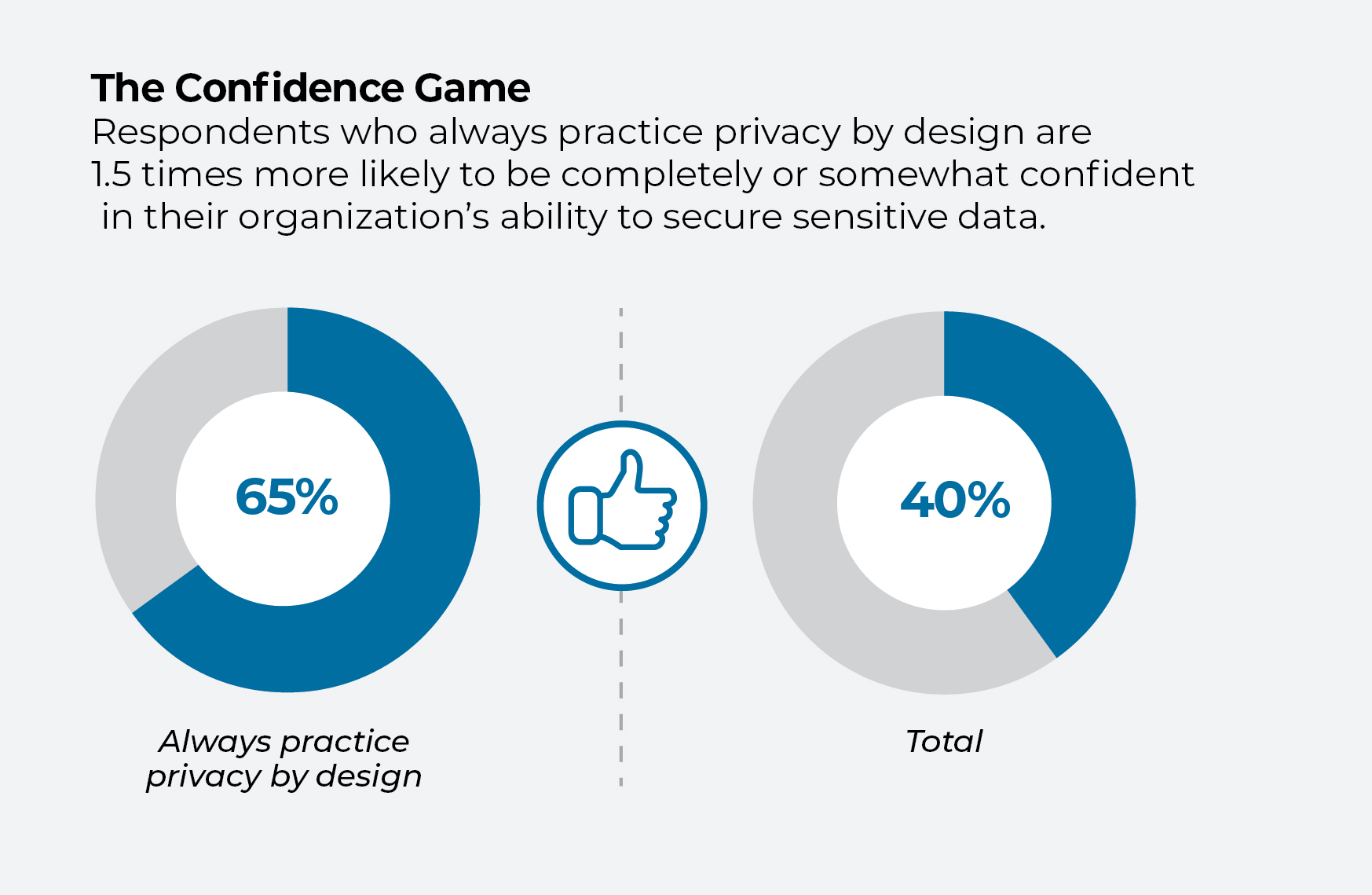

Though privacy by design may require more staff and/or more focus on staff training, the benefits are notable. Enterprises that practice privacy by design have the advantage, ISACA says. Almost two-thirds of those companies are completely or somewhat confident in their ability to ensure the privacy of sensitive data, according to the survey, compared to 40 percent of all respondents.

Data security starts with protecting what’s most sensitive

In the meantime, privacy professionals in an understaffed company should look to prioritize their time and focus on areas where the data is especially sensitive.

“Maybe there’s something that’s going to be touching health information,” she says. That’s more important for privacy professionals to be involved with than, say, a marketing effort that’s collecting email addresses. Even so, she says privacy professionals “should really examine all of the projects that are happening.”

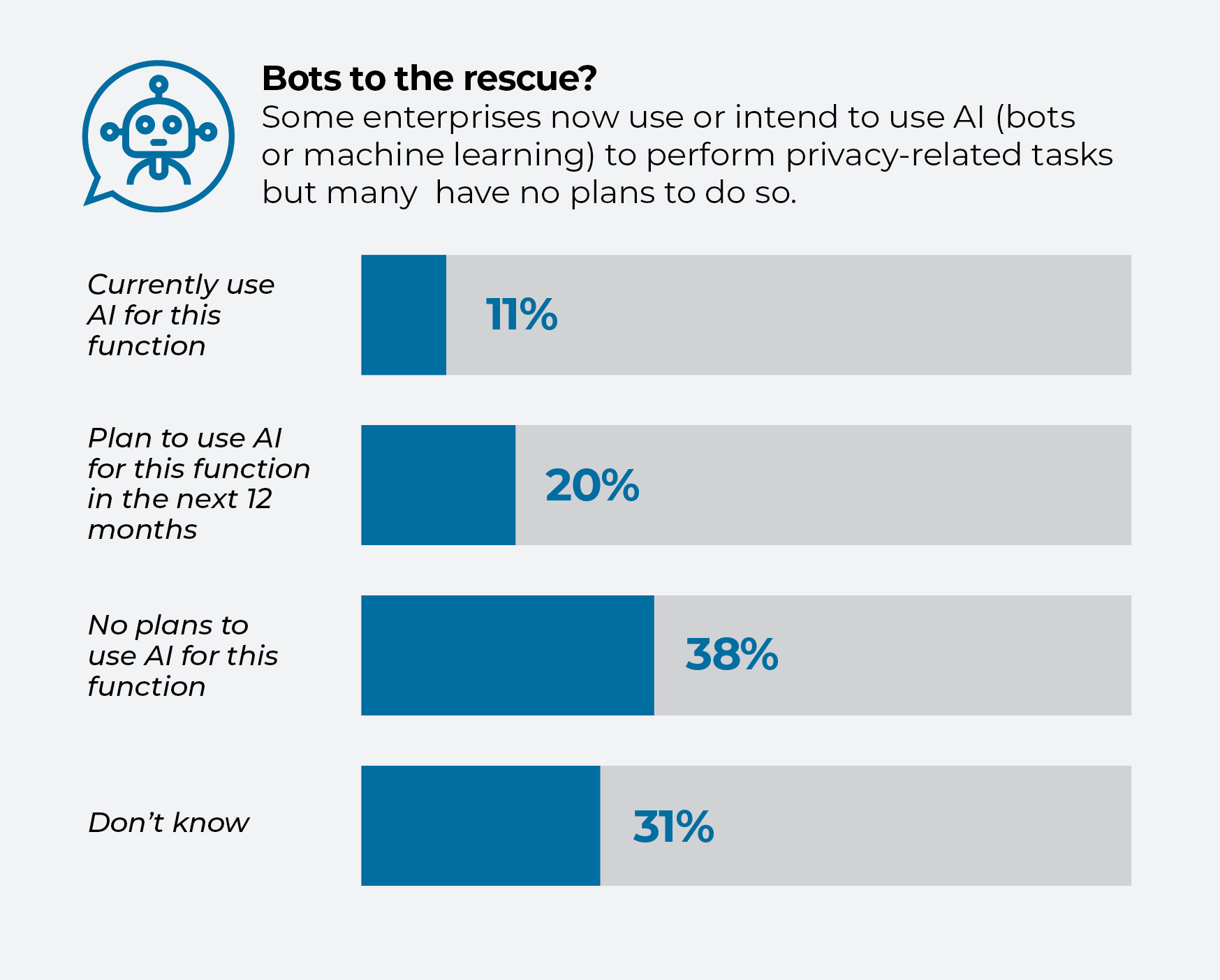

One thing that likely won’t solve the staffing shortage is artificial intelligence. In ISACA’s 2022 survey, about one in five respondents said they planned to start using AI in the next 12 months. But this time the number was only 11 percent.

“I don’t know if privacy professionals are comfortable just yet turning that over to something automated,” Kazi says. AI may be great for automatic replies to email, but when it comes to privacy, the stakes may be too high.

“If done improperly,” she says, “it could be so catastrophic.”